BUSINESS soil fumigation

Maintenance of healthy soil is essential for sustainable agricultural productivity.

CAN FUMIGATION

always provide the desired benefits?

Pre-planting soil fumigation using metham sodium (MS) is a customary practice in the WA potato industry to control weeds, soilborne pathogens, and nematodes. Growers’ reliance stems from a perception that MS application improves packout yield and/or quality.

Words Wossen Mengesha (Research Scientist, PhD, Plant Pathology Insects and Disease, Horticulture, DPIRD), Neil Lantzke (Senior research scientist — Horticulture, Intensive and Irrigated Plant Systems, DPIRD) and Dr Julia Grassl (Principal Research Scientist, Insects and Disease, Horticulture, Intensive and Irrigated Plant Systems, DPIRD)

In some previous studies, successive application of MS has shown diminished effectiveness in control of Verticillium wilt in potato1 , or showed no difference on the level of Powdery scab incidence, on daughter tubers, when fumigated and unfumigated plots were assessed2 .

Maintenance of healthy soil is essential for sustainable agricultural productivity. Healthy soil allows healthy plant growth across the year with little fluctuation between seasons and sustaining productivity even in the presence of biotic stressors3 .

Repeated application of MS is widely reported to harm beneficial soil microorganisms. These microbes play key roles in soil functions including nutrient cycling, making nutrients available to plants, and helping soils naturally suppress diseases.

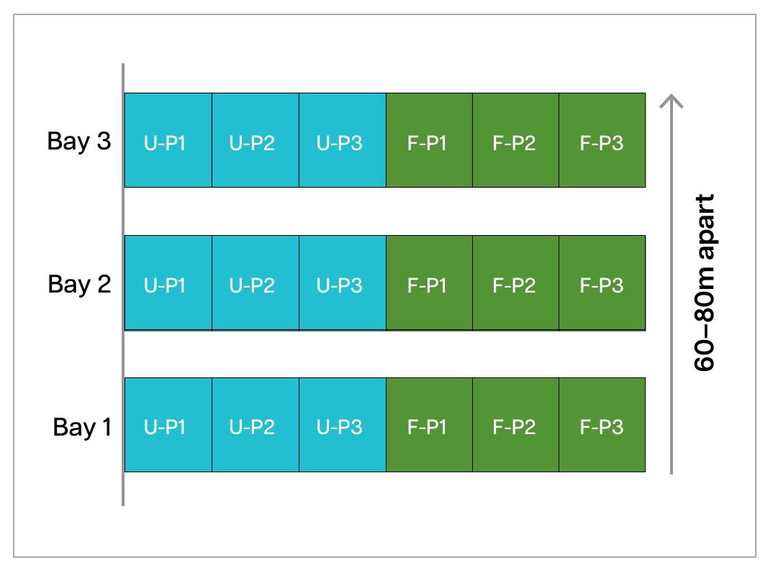

To investigate the effects of MS fumigation on harmful pathogens and beneficial microbes within the whole soil microbiome, we conducted a small preliminary trial comparing fumigated and unfumigated areas across three bays. Each bay contained Fumigated (F) and Unfumigated (UF) field-length strips, subdivided into three 9 m² plots (see Figure 1).

Three potato varieties were grown under commercial condition in Myalup, WA. We assessed soil inoculum levels with Predicta Pt, marketable yield, grade distribution, and soil-borne blemishes on the tubers. Additionally, we measured and compared the overall soil microbial community, using next-generation DNA sequencing. The key findings are summarised below.

FIGURE 1. Paired strip-trial setup. Each bay acted as a block to control for field variation, and we compared treatment effects using a paired t-test)

Marketable yield response to fumigation

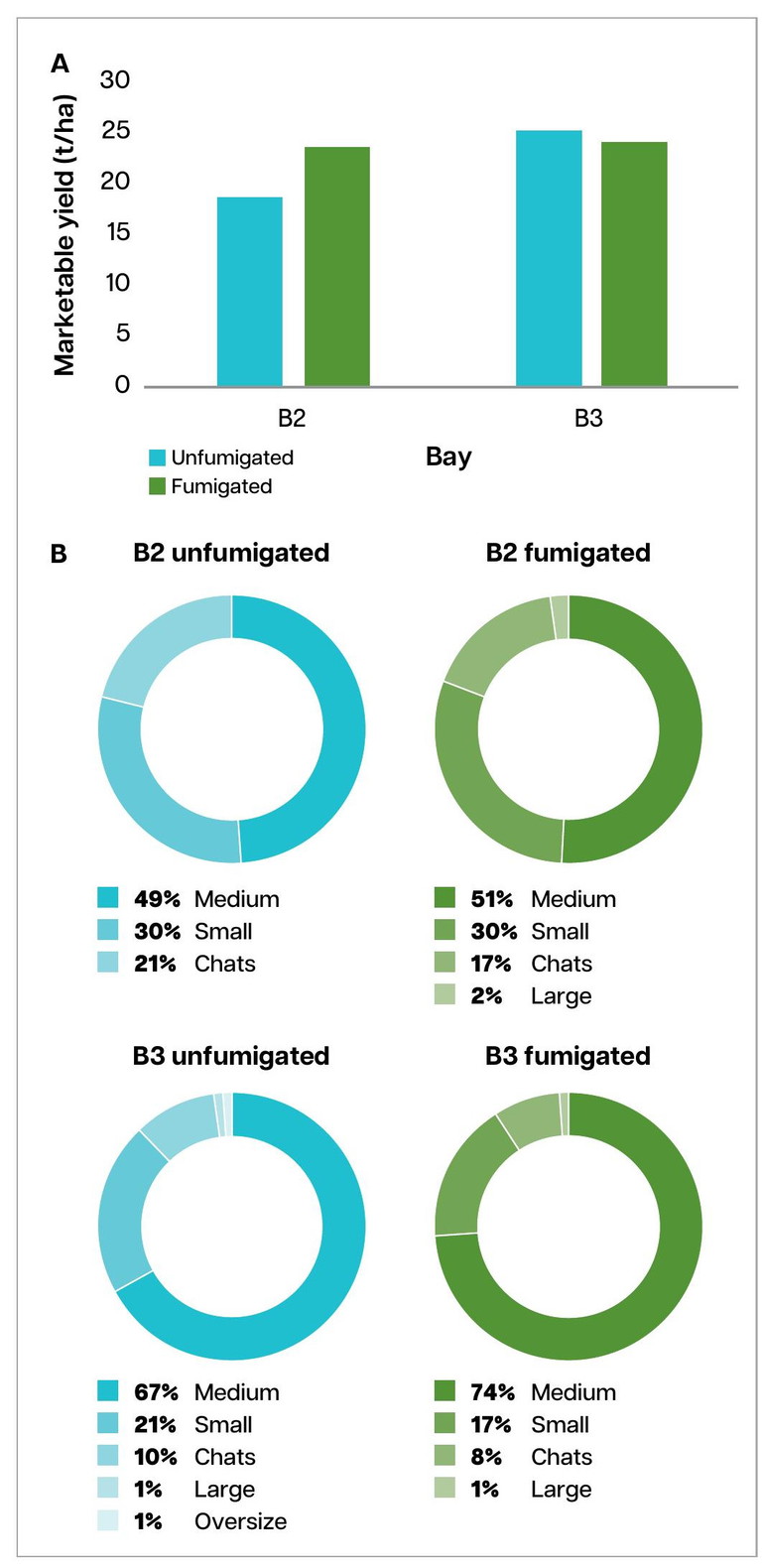

Marketable yield varied a lot between the three bays, but fumigation with MS did not produce a significant yield benefit (paired bay-blocked t-test, p = 0.64) (Figure 2a). In Bay 1, both fumigated (F) and unfumigated (UF) plots yielded poorly due to poor germination and establishment, which was unrelated to fumigation treatment (data is not shown).

In Bay 2, fumigation produced slightly higher marketable yield whereas unfumigated plots reached slightly higher yield in Bay 3. Overall, fumigation had no meaningful impact on yield.

Grade composition distributions (Chats, Small, Medium, Large, Oversize) (Figure 2b) were also consistent between fumigated and unfumigated plots. In both treatments, medium-sized tubers made up 50–70 % of the total yield.

Soil pathogens inoculum levels

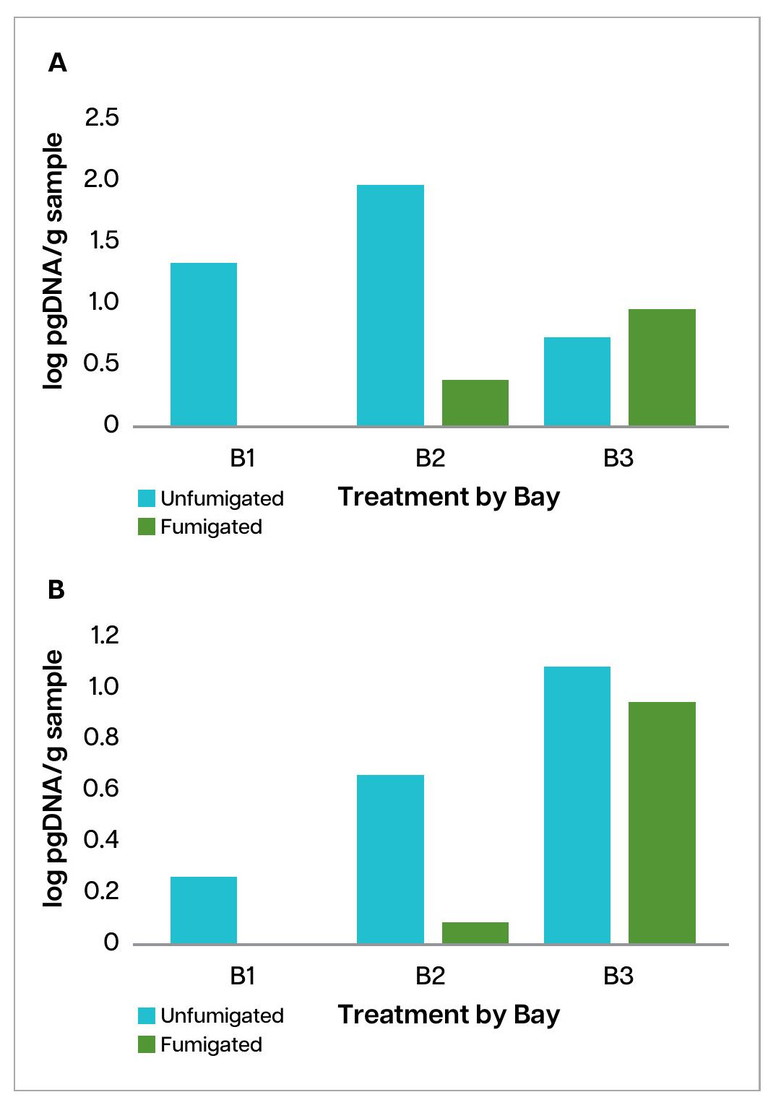

In this trial, we used Predicta Pt to assess the effect of MS fumigation on pathogen soil inoculum levels by testing soil before planting and again after fumigation. Predicta Pt identified two key pathogens of concern: Colletotrichum coccodes (Black dot) and Spongospora subterranea (Powdery scab).

Fumigation reduced soil inoculum levels of both pathogens in Bays 1 and 2 (Figure 3a and b). However, overall inoculum levels were already low in the paddock and considered low-risk for disease development, except for C. coccodes in the unfumigated plot of Bay 2.

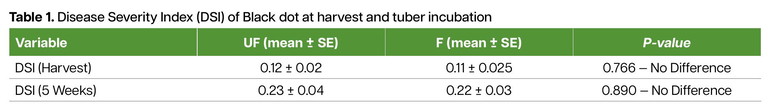

Despite these small reductions in soil inoculum, there was no difference in disease severity at harvest or after five weeks of storage (Table 1). Disease severity index (DSI) scores for Black dot were low and similar in both fumigated (F) and unfumigated (UF) plots. This suggests disease pressure was minimal, and fumigation did not provide a noticeable advantage.

Powdery scab incidence was extremely low across all bays, consistent with the low pre-plant inoculum levels, regardless of fumigation treatment.

Overall, while fumigation caused a short-term drop in soil inoculum, this did not translate into meaningful disease or quality benefits under the conditions of this trial.

FIGURE 2. Potato marketable yield (t/ha) estimated based on three plots of F and three plots of UF from the two Bays (a). Grade distribution in each bay (B2, B3) for fumigated (F) and unfumigated (UF) strips (b). Due to poor germination and performance, the data from Bay 1 was not included.

FIGURE 3. Changes in soil inoculum between fumigated and unfumigated plots of a) Colletotrichum coccodes (Black dot) and b) Spongospora subterranea (P. scab)

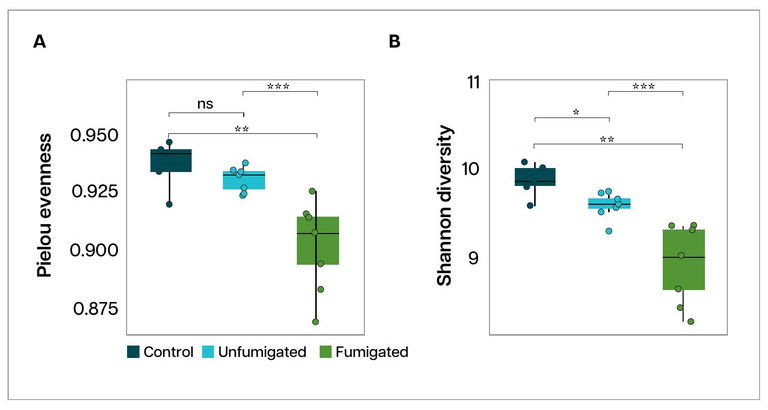

FIGURE 4. Balanced microbial distribution (Pielou evenness) and microbial richness (Shannon diversity) was reduced in soils of fumigated plots compared to unfumigated plots (fallow for 3 years) and more so compared to control paddocks (uncultivated land nearby).

Effects of MS fumigation on the soil microbiome

Soil tests from the fumigated plots showed a clear drop in microbial diversity compared with unfumigated soil. In simple terms, fumigation reduced the range and balance of beneficial soil microbes.

A diverse soil microbiome is important because it helps support crop growth and naturally suppresses disease-causing organisms.

When microbial diversity falls, harmful pathogens can become more dominant, which can increase the risk of crop infection. In this trial, MS fumigation lowered both Shannon Diversity and Evenness, meaning the number and balance of different microbes in the soil were significantly reduced (Figure 4). Over time, this may weaken the soil’s natural disease-suppressive ability.

We also compared the trial bays with a nearby uncultivated area. Both the fumigated and unfumigated potato plots had lower microbial diversity than the uncultivated soil. This reinforces the need for good paddock management practices to restore and maintain soil biological health in potato-growing systems.

Overall, this demonstration showed MS fumigation did not deliver measurable benefits in marketable yield, tuber grade distribution, or Black dot and Powdery scab control under Myalup growing condition in this one-season trial.

Although fumigation temporarily reduced soil inoculum levels, this did not result in meaningful improvements in disease levels or tuber quality.

While fumigation did provide weed suppression, the negative impact on soil health and the availability of far cheaper and safer weed-control options make it difficult to justify MS use based on weed management alone. Additionally, MS does not remove the need for fungicides, insecticides, or herbicides during the crop, meaning growers still face repeated seasonal costs.

It is important to note that this was a small, single-season study in one location during late summer. More research is needed across multiple sites, soil types, and seasons to fully understand the effects of MS on soil health and its true value to potato production. Continuing to explore and refine alternative crop protection and soil-health strategies remains essential for both productive and sustainable potato systems.

1 Triky-Dotan, S., Austerweil, M., Steiner, B., Peretz-Alon, Y., Katan, J., & Gamliel, A. (2009). Accelerated degradation of metam-sodium in soil and consequences for root-disease management. Phytopathology, 99(4), 362–368.

2 Shan, S., Lankau, R. A., & Ruark, M. D. (2024). Metam sodium fumigation in potato production systems has varying effects on soil health indicators. Field Crops Research, 310, 109353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2024.109353

3 Trivedi, P., Leach, J. E., Tringe, S. G., Sa, T., & Singh, B. K. (2020). Plant–microbiome interactions: from community assembly to plant health. Nature reviews. Microbiology, 18(11), 607-621. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0412-1

MORE INFORMATION

For more information on this project please contact:

• Wossen Mengesha: 0413 654 096, wossen.mengesha@ dpird.wa.gov.au

• Dr Julia Grassl: 0405 170 150, Julia.Grassl@dpird.wa.gov.au

• Neil Lantzke: 0429 990 439, Neil.Lantzke@dpird.wa.gov.au